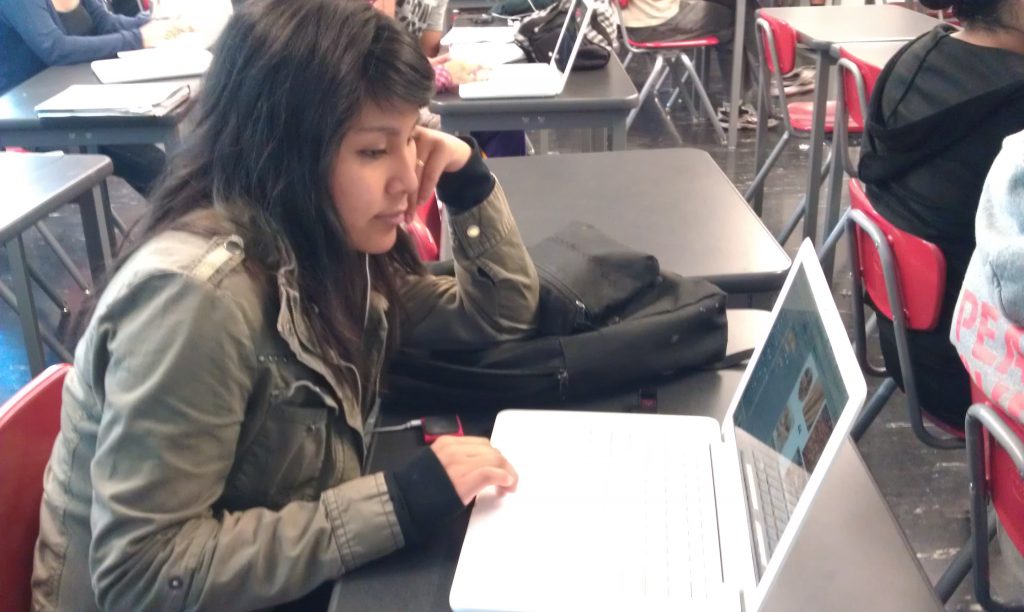

Roya Amigh and I shared cake wrapped in tin foil and held mugs of tea to warm our hands on a cold, rainy day in Cambridge while we stared at the object in question on the screen of my laptop: Record no. 1138A36. Embroidered Shelf Cover. Belonged to Munir al-Muluk Jahandari. Amigh and I were meeting to discuss her involvement in Women’s Worlds in Qajar Iran, a digital archive on the web directed by Afsaneh Najmabadi, Francis Lee Higginson Professor of History and of Studies of Women, Gender, and Sexuality.

Detail of Embroidered Shelf-cover. Record no. 1138A36.WWQI

“There is enough line, enough texture, enough color.” Amigh, who is a painter and has an MFA in Studio Art from Boston University, paused to consider her choice. I had asked her to promote her favorite image of the more than thirty thousand items “held” in the digital archive of Women’s Worlds of Qajar Iran (WWQI). Amigh has been editing digital images for WWQI for almost a year now. Speaking of her experience with editing these images on Photoshop, Amigh explains, “When I looked at the images to edit, I thought to myself, oh my gosh, these are beautiful…It just satisfied me visually. And not only the image, but also the calligraphy in the letters. The phrases in the love letters. After a while though, as I was working through a collection it became about getting to know the people in the pictures, or the owners of the objects.” Soon, this process of discovery led her to question her preconceived ideas about the lives of women in Iran, during the time period bracketed by the Qajar dynasty. “I took history classes in Iran, many, and working with this material destroyed my ideas about women during this time period in Iran.”

Coincidentally, Azadeh Tajpour, also a painter with a MFA in studio art and an MA in Art History from Claremont University and California State University, respectively, had also chosen the same item, the embroidered shelf cover, when I asked her to describe her favorite item. Tajpour focused on another detail, of the man swinging a brazier of rue to ward off the evil eye.

Detail of Embroidered Shelf-cover. Record no. 1138A36.WWQI

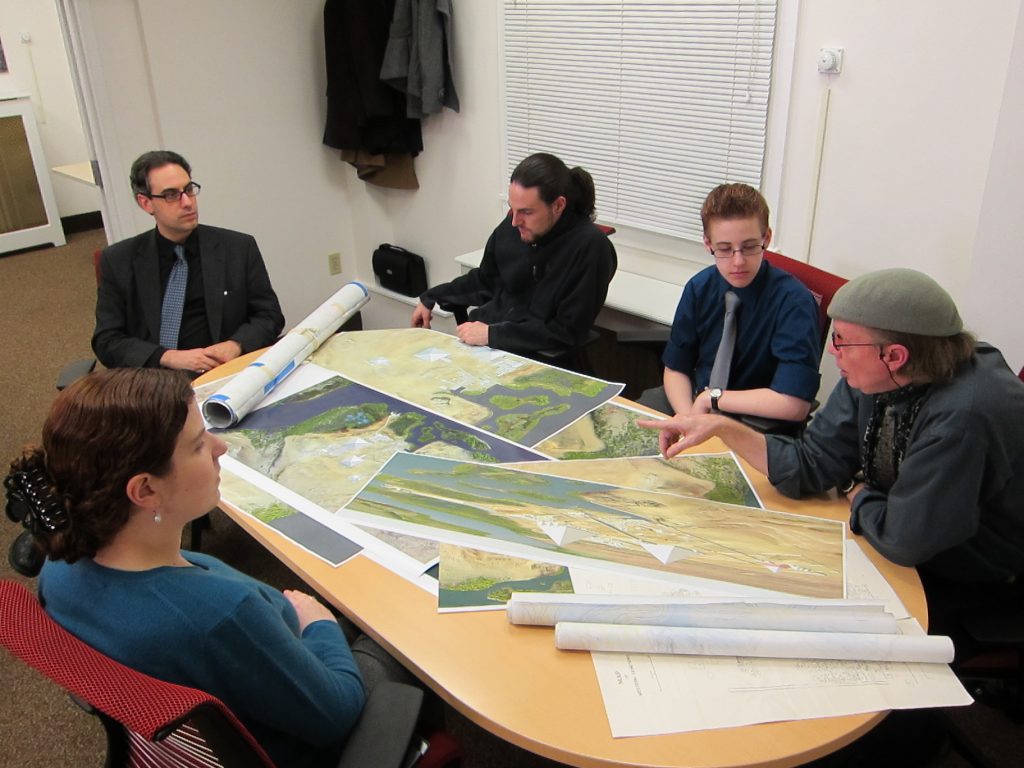

Tajpour has been cataloging and translating for WWQI since August 2011. She described some of the detective work involved in creating the records and editing the digital images for the web. The embroidered shelf cover, she notes, belonged to Ashrafi, the Lady of Ashraf, as she was known (picture below). Disentangling family ties and inheritance claims gave her some insight into the life and times of a powerful widow and her immediate family members. Tajpour glosses the family picture for me:

She was a widow after her husband was murdered and was left with sizable property. We have the images of her accounting books which she kept. She, her mother and her mother-in-law, we can follow the transfer and inheritance of property among women. When we saw that the mother had married her daughter’s father in law, at first we thought it was a mistake, but then we were able to piece together how the marriage came about. After the daughter was left a widow, her mother came to live with her. So, there is a picture of the three women, the widowed daughter, and her two mothers in law (co-wives), one of which is also her biological mother.

From left to right: Muhammad Ashrafi (son of Banu-yi Ashraf), Fatimah Khanum (mother of Musa Khan Ashraf al-Mulk), Musa Ashrafi (son of Banu-yi Ashraf), Banu-yi Ashraf, Zibandah Khanum Shahzadah Banu (mother of Banu-yi Ashraf), Maryam Ashrafi (daughter of Banu-yi Ashraf), Ahmad Ashrafi (son of Banu-yi Ashraf)

Tajpour was also surprised that she had owned a backgammon table, a game often associated with men. Soon our conversation shifted to speculation, as we imagined how playing might have allowed Ashrafi to hone her business skills. By measuring the strategies of her opponents at the table she might gain insight into their qualities as partner or competitors. Najmabadi notes that these images have inspired the short stories and vignettes of Shermin Naderi, a writer of historical fiction, who references the WWQI archive in her work.

Undermining stereotypes about women during the Qajar period was one of the main goals of Afsaneh Najmabadi when she started to conceive of the WWQI project ten years ago. Yet even she has marveled at the amount and quality of the material they have been able to scan and photograph for the site.

When we started in 2003, we thought it would be a shot in the dark, that we would collect at most 1000 images. And it just took on a life of its own. The amount of material that we have come across and the quality of the materials surprised me. Bundles of letters exchanged between husband and wife, love letters. In my wildest dreams I did not think we would come across such things. Right now we are close to 30,000 images and I don’t know how many are being processed right now or waiting to be processed. It is truly mind boggling. Our only limitations are budget.

Najmabadi and her team have been overwhelmed by the generosity of families in Iran, Australia, Switzerland, the United States, England, etc., who have given permission for their beloved objects to be scanned and made available to the world on the digital archive. Since WWQI is not only interested in the women of the Qajar dynasty but of all women living in the domain ruled by the dynasty, it is not difficult to imagine the possibility that every household in Iran and among Iranian diasporas might have an object in their homes that belongs to a family member or an ancestor who hails back to the Qajar period. Right now the project has a waiting list of families, within Iran and around the world, that wish to contribute family heirlooms to the digital archive.

What people have to say about their family heirlooms may also form part of the archive. What emerged as an ad hoc process for cataloging purposes, has become another resource for WWQI users, present and future. Najmabadi explains,

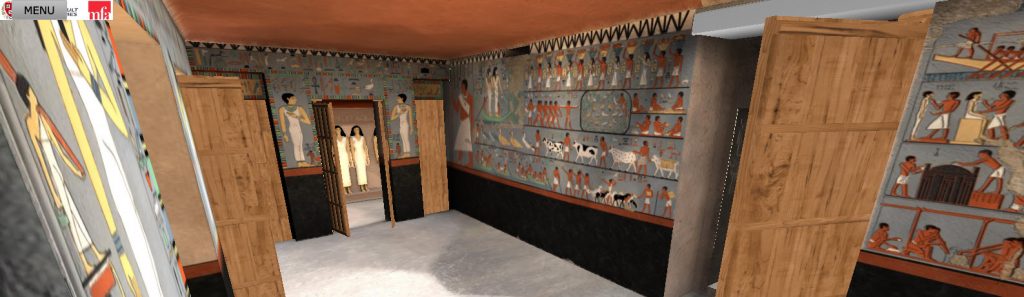

We would record family members talking about the objects in order to facilitate record making. But one of my graduate students, Ramyar Rossoukh, a doctoral student in anthropology and the real mind behind WWQI design, said, we should be using the clips themselves. Now, if we have the person’s permission, we provide these audio clips along with the images of the object in question. That is one of the benefits of the digital archive, that you can connect voice to object to picture to memory. That was another thing that “happened” which we now do very consciously.

I confess to Najmabadi the compulsive aspect of searches on her site. From experience, the tags and categories offer endless ramifications and connections for the user. The result is that the site can engross its users for hours. Najmabadi credits Rossoukh for the sites’ “searchability and user friendly absorption.” Najmabadi adds, “He was set on producing something that was visually attractive and grabs people…Something else that we wanted: An archive to be visually stunning, worthy of the material that it showcases. Clocks, backgammon tables, handwriting, we wanted that to be reflected in the design of the site.”

Screenshot of the “Browse” page for the WWQI site.

Each image with its recorded voice and tags on the WWQI site is not only a world unto itself but also a key to an ever expanding universe of connections, the “six degrees of Kevin Bacon” of women’s lives in Iran, present, past and future. Roya Amigh closes our interview with a lead to her own family: “My dad has found some materials that we are thinking to contribute, from his grandmother. She was very powerful. I’ve seen a picture of her. She could touch your soul. She had the power to agree or disagree, to say I don’t want this or that.”

Here’s to the women behind Women’s Worlds in Qajar Iran.

WWQI would like to thank Tara Murphy without whom the project would never have materialized and Cory Paulsen for her sustained supportive work.